What is JupyterLab?¶

It’s not just an interface for working with Notebooks. The Notebook interface has been around since 2011, and in 2018, JupyterLab was introduced to provide a more comprehensive environment, like an operating system, for interactive computation.

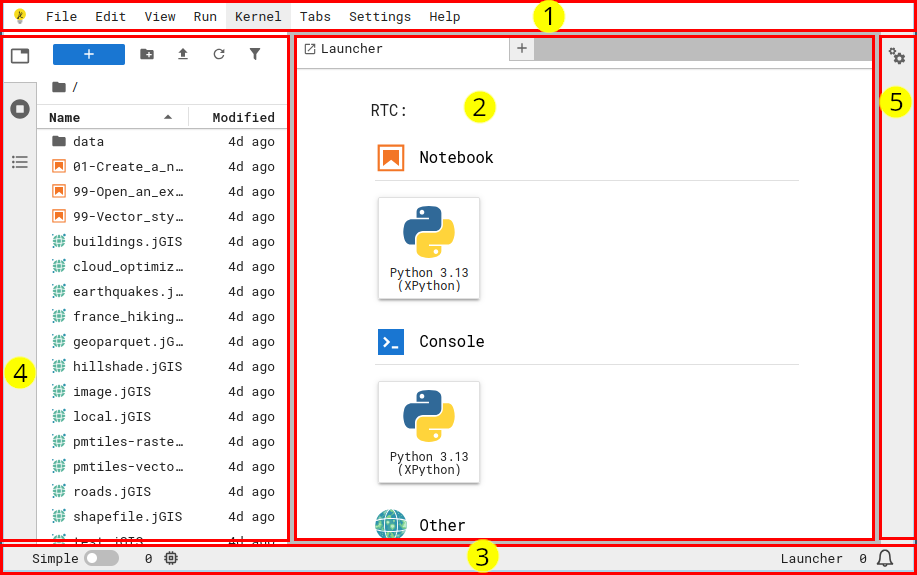

The JupyterLab interface¶

We assume you’ve seen this interface before, but let’s quickly go over the technical terms for the components of the interface so we’re all on the same page.

Why learn to write extensions?¶

The power of JupyterLab comes from its extensibility. You can install helpful tools, like version control, visualization improvements, addons to convert notebooks to other formats, AI assistants, or highly specializied toolkits for domains like quantum computing, geology, or astronomy.

There are over 600 extensions compatible with the latest version of JupyterLab at the time of this workshop.

Extensions and plugins and widgets -- oh, my!¶

While they sound similar, extensions and plugins serve different purposes.

Plugins are JupyterLab’s fundamental building blocks which define

functionality and business logic.

Extensions are the delivery mechanism or “container” for plugins.

Extensions are the thing that end-users pip install.

End-users care about extensions, and developers care about plugins.

A widget is a user interface component provided by a plugin, either for the end user to display (e.g. an interactive visualization of data) or for JupyterLab to display (e.g. a document viewer that opens when you double-click a particular file type).

Core extensions¶

JupyterLab itself is a collection of extensions. For example, the Notebook editor, file browser, and code console are all core extensions that are bundled with JupyterLab.

Extension categories¶

Server extension¶

Extensions that run on the JupyterLab server, which means it has access to the same hardware as JupyterLab and can, for example, load data from disk and perform computations.

Server extensions are written in Python.

Examples¶

jupyter

-server -proxy enables running, supervising, and proxying additional web services within a JupyterLab deployment. nbgitpuller enables automated fetching of content in a Git repository into JupyterLab from a special URL. Especially useful for teachers to provide their students with access to educational materials in a JupyterHub by clicking a single link.

Frontend extension¶

Extensions that run in the JupyterLab frontend (i.e. the user’s browser), which means it can change anything about the appearance of JupyterLab and provide new widgets for display and/or interactions.

These are sometimes referred to as “lab extensions”.

Frontend extensions are written in JavaScript or TypeScript.

Examples¶

jupyterthemes provides custom appearances for Notebooks.

...

Frontend and server¶

A very common pattern is extensions which combine frontend and server extensions to provide new interface features which trigger behavior on the server.

Examples¶

jupyterlab-git provides visual git management.

jupyter

-resource -usage displays information about kernel resource (CPU, RAM) usage in the frontend. gator enables graphical management of conda/mamba environments.

JupyterGIS (beta) provides a Geospatial Information System (GIS) interface for working with geospatial data.

...

MIME renderer extension (a.k.a. “mimetype” extension)¶

Extensions that tell Jupyter how to view information in a specific file type (MIME type).

These are a special case of frontend extensions which map a widget viewer with the supported file MIME type strings.

Examples¶

jupyterlab-geojson enables double-clicking on GeoJSON files and viewing them on a JupyterLab-native map viewer.

...